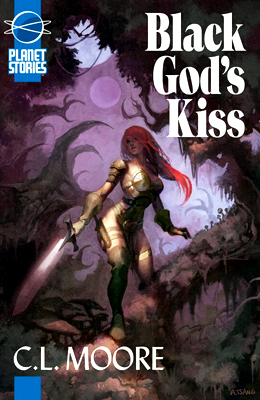

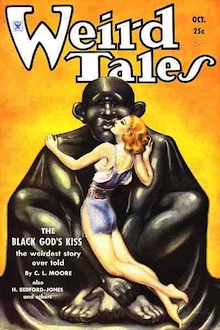

Lately, I’ve been really interested in Sword and Sorcery fantasy, both in its contemporary and original expression. As regards the latter, I’ve just read—and been blown away by—C.L. Moore’s Black God’s Kiss, a collection from Planet Stories that gathers together all six of her Jirel of Joiry tales, which originally appeared (mostly) in the pages of Weird Tales magazine between 1934 and 1939. Now, I confess, I never finished The Lord of the Rings, and never read Brooks, Goodkind or Jordan. But growing up I devoured everything I could get by Howard, Leiber, and Moorcock. As well as the “sword and planet” stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs. So it’s a glaring hole in my sword and sorcery education that I’ve never read C.L. Moore and the utterly seminal Black God’s Kiss before now.

Reading Moore for the first time, I was struck by how well she reconciled Howard to Lovecraft and married the sensibilities of these two ground-breaking masters of fantasy into one narrative. Jirel of Joiry is a female Conan, whose defining attribute is probably her temper, and the fact that if she perceives a slight she will hound the offender to hell and back for the chance to draw blood (that’s the plot of at least three of these stories). The Queen of a fictitious French realm, she’s a better fighter than any man under her command, and definitely leads from the front (we don’t learn much about her retainers apart from a few names. They are mostly props and the focus is usually on getting Jirel swiftly into solo action). But on that “hell and back” comment—Jirel pursues her vengeance into a host of alternate dimensions (it was refreshing to see in a later story her recognition that all this dimension-hoping had left a taint upon her), and while she passes all the wonders and horrors bye with the narrow-mindedness of a bloodhound, Moore’s lavish description of same is what makes the tales positively Lovecraftian.

In “Black God’s Kiss,” the landscape Jirel enters—a hellish world the portal to which is accessible from within Jirel’s own castle—isn’t a conventional Christian hell at all, but a weird, otherworldly realm seen dimly under strange stars and peopled by horrific entities dwelling in strange places (one can almost hear the word “non-Euclidean” in between the lines). Jirel has come here seeking a weapon to slay a usurper to her kingdom, though given the lack of traditional demons and devils, why she supposes anything in this dimension would care for such traditional bargains is unclear. Nonetheless, she finds the means in the black god’s kiss of the title, one of the creepiest moments surely in fantasy fiction, and, quite possibly, the inspiration for a similarly striking bit of ickiness in China Mieville’s The Scar.

The follow up, “Black God’s Shadow,” is similarly impressive in its imagery but less successful than its predecessor. Jirel returns to the netherworld beneath Joiry to rescue a soul she feels responsible for sending there. One can almost hear her editor saying, “That was a great story, give me one just like it.” But more troubling to me is that in this, the Lovecraftian other world, which was so wonderfully inexplicable before, is recast firmly as a place for the punishment of sinners. While still not quite a recognizable Christian afterlife, it looses something of its unknowable weirdness in being given such an understandable function. Still a marvelous story for its imagery though.

The follow up, “Black God’s Shadow,” is similarly impressive in its imagery but less successful than its predecessor. Jirel returns to the netherworld beneath Joiry to rescue a soul she feels responsible for sending there. One can almost hear her editor saying, “That was a great story, give me one just like it.” But more troubling to me is that in this, the Lovecraftian other world, which was so wonderfully inexplicable before, is recast firmly as a place for the punishment of sinners. While still not quite a recognizable Christian afterlife, it looses something of its unknowable weirdness in being given such an understandable function. Still a marvelous story for its imagery though.

In “Jirel Meets Magic,” she pursues a magician who has slighted her into yet another dimension, only to find the magician is the consort of a powerful sorceress. The most amusing aspect of this tale to me is the way that Jirel strides past half a hundred wonders utterly blind to anything but her ego-driven need for revenge. No muscle bound male barbarian could have done it better.

In “The Dark Land” Jirel finally gets bested, at least in backstory. We open with her on her deathbed, but she is rescued, spirited away to yet another dimension, and restored by a supernatural entity that wants her fierceness for his perfect mate. Characteristically unyielding, she challenges him, and he stupidly agrees to relinquish her if she can find a way to accomplish the impossible and kill him. This is the most fantastical of all the tales, with very little reference points for those of us in the real world to grok and hold on to. It’s a magical world of mind-over-matter, where every bit of the landscape is under the sway of a nonhuman force. For some strange reason, it reminded me of the TNG episode in which Tasha Yar dies. I liked it a bit more than that, but it’s not the strongest story of the book.

“Hellsgarde,” the penultimate story in the book, was my second favorite story of the collection, possibly tied for first. The last to be written chronologically, it feels the most modern. Moore’s somewhat purple prose, which is more her strength than her weakness really, is the most restrained here. Likewise, the plot is the most complex and, well, makes the most sense. Jirel’s men are being held-hostage in an impregnable fortress, and its owner has forced Jirel to enter a haunted castle and retrieve a fabled treasure. But once there, she encounters another party with sinister interests that dovetail with her own. The gathering, and the revelation of their ultimate intent, felt very “Moorcockian” to me, though, of course, I am referencing writers I encountered first who actually came after, and knowing of Moorcock’s appreciation of Moore it’s not unthinkable that she was an influence. This was the last tale of Jirel Moore would pen, though she wrote other stories, and then screenplays for several more decades (mostly with husband Henry Kuttner under the pseudonyms Lewis Padgett and Lawrence O’Donnell). It’s a shame she didn’t carry Jirel’s adventures forward, as Leiber did with Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, because I would have liked to see where this character evolved given time. As it stands, “Hellsgarde” is probably the most film-able of all of the Jirel tales (and, listen up Hollywood, because this would make a great follow up to that Solomon Kane film you’ve got coming out). I suspect it will be the first one I reread as well.

The final tale, “Quest of the Starstone,” is a collaboration with Kuttner, and a cross-over with Moore’s other great creation, Northwest Smith (who was the original Han Solo way before Han Solo). I’ve not read the Smith stories yet (though I have them and hope to do so soon), and found this to be fun, but not really as strong, or as “authentic” as the other tales. Basically, it suffers from the same thing that all superhero crossovers do, in that the story is just an excuse to get two popular heroes to fight, then make up and clobber a bad guy. I would have placed this in its chronological order, as “Hellsgarde” would make for a stronger finish, but understand Planet Stories’ reasons for wanting to leave this as a hook into Moore’s other collection. And that’s a minor quibble for a powerful book.

All these stories, taken together, are a powerful look at an important figure in early sword and sorcery. Moore was both one of the fantasy’s first female authors and Jirel one of its first female characters. She was unique in a time when our genre wasn’t full of Buffy and Xena-knock offs, a pioneer whose influence is still being felt (I spotted at least one more image I think inspired Miéville, though I don’t know this for a fact.) I can’t believe its take me this long to read it, but thank the black gods I have now. This is great stuff, and my fantasy education was woefully incomplete without it. So is yours…

Lou Anders is the three-time Hugo-nominated editor of Pyr books, as well as the editor of seven critically-acclaimed anthologies, the latest being Fast Forward 2. More relevant to this post, next summer will see the release of his co-edited, massive sword and sorcery anthology, Swords & Dark Magic. Lou recently won a Chesley Award for Best Art Director, and is pretty chuffed about that too. Visit him online at his blog, Bowing to the Future.